Waiting for Godot (2013)

Performances

Mar 22, 2013 -

Apr 20, 2013

“All of old. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

Cast & Personnel

Director

Dramaturgy

Cast

Scenic Design

Costume Design

Lighting Design

Sound Design

Prop Design

Stage Manager

The Play

Last year Catastrophic artistic director Jason Nodler directed Greg Dean and Troy Schulze in an award-winning production of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, which led the Houston Chronicle to ask, “Does Beckett Get Any Better?” and the Houston Press to declare “The magnificent Endgame gets magnificent treatment from Catastrophic.”

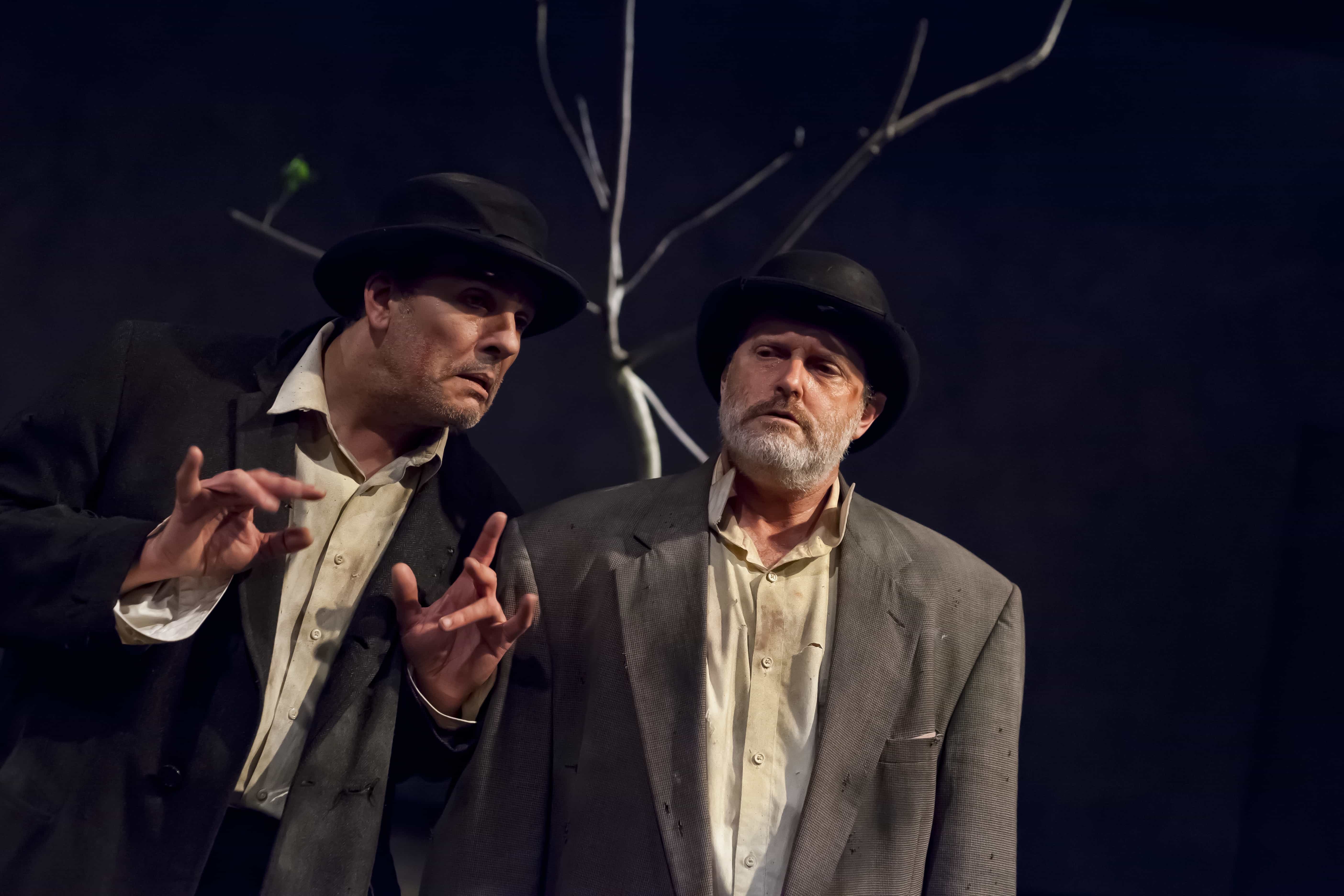

This year Nodler directs Dean and Schulze again, along with Charlie Scott and Kyle Sturdivant, in the most enduring play from the unwitting inventor of the Theatre of the Absurd.

There is a common misunderstanding of Beckett’s work that goes something like this: his plays are heady and serious, and his message is dreary. In truth there were three things that Beckett loved above all else: his wife Suzanne, a good Irish Whisky, and the comedy styling’s of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. So much more than a messenger of gloom, Beckett also belonged to the music hall tradition. He loved to laugh at a proper pratfall. As he has Nell say in Endgame, “nothing is funnier than unhappiness.”

That a woman laughs on one side of the audience while a man cries on the other, at the selfsame line, is unique to a Beckett play.

It would be virtually impossible to overstate the importance of Waiting for Godot as it relates to the history of world theatre, art, and philosophy. But let’s leave that aside for a moment because it would also be impossible to overstate the new ways in which Godot taught us to laugh, and also to cry.

In fact Beckett’s early plays are perhaps the only tragicomedies truly deserving of the title. For Beckett melted together those famously outmoded theatre masks as if to say that life is not happy or sad; life is short and we are dying so let’s have a laugh on our way out. Yes, death is nearing always, our prospects are bleak, and our prognoses are bleaker, but we are here. And we must find our amusements along the way, if only to pass the time. Vladimir, Estragon, Pozzo, and Lucky do a fine job of entertaining themselves and us, in spite of (or perhaps owing to) the tedium of their local situation.

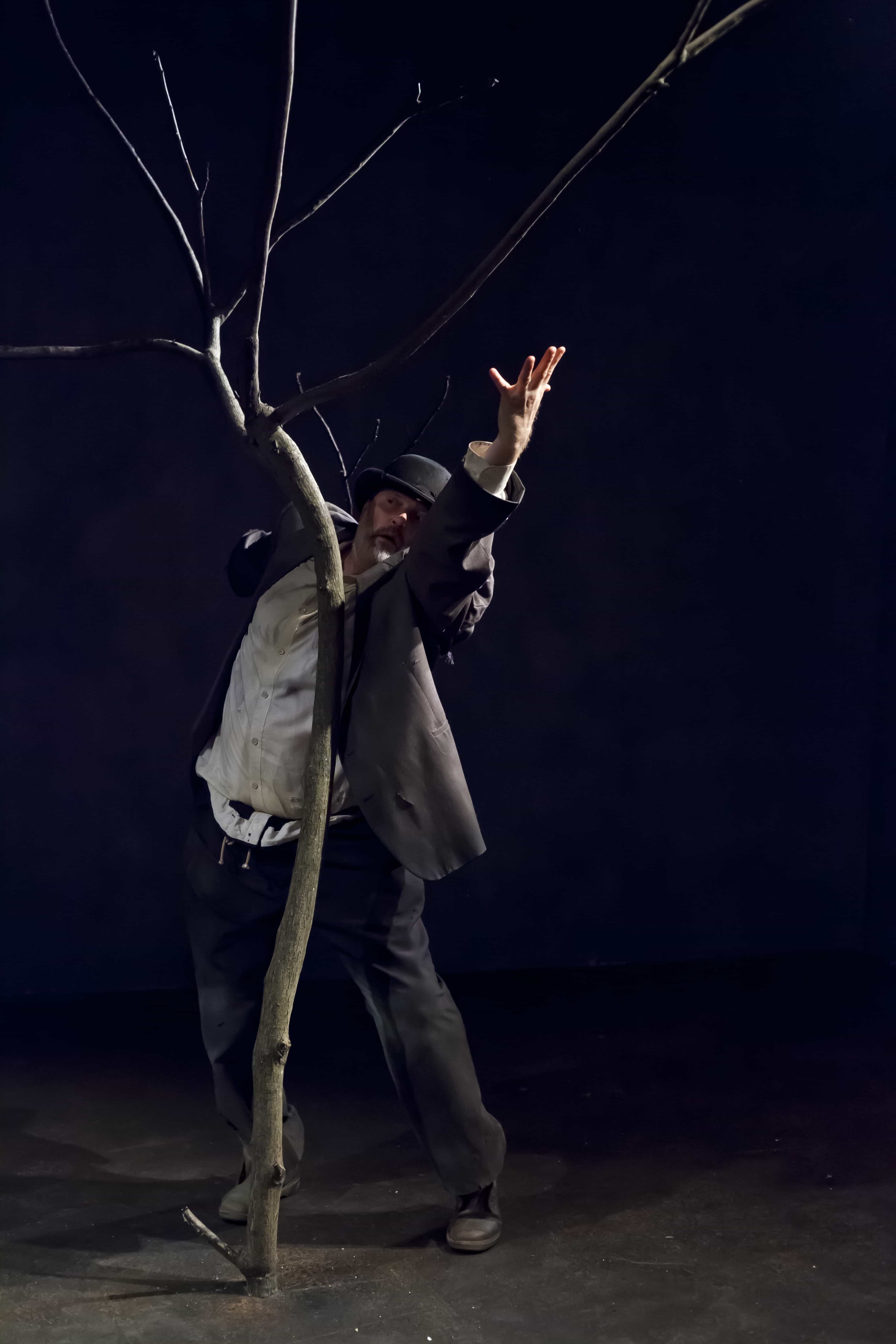

Nodler says, “I was only 27 years old the first time I took a crack at the seminal work of the artist that most profoundly affected the course of my life. I’ve been waiting 44 years now for my own Godot to arrive. He hasn’t of course—it’s not his nature—but I felt it might be time to wander around in that particular dark again… to stand unknowing on a country road with barely a rock and a tree and a sky to guide us.”

Whether developing new work for the theatre, introducing contemporary playwrights to Houston audiences, or producing the classics of the avant-garde theatre movement that continues today, The Catastrophic Theatre is guided always by Beckett’s creed, by this creed:

We cannot think of any better play with which to inaugurate our new theatre.

The Playwright

SAMUEL BECKETT was an Irish avant-garde novelist, playwright, theatre director, and poet, who lived in Paris for most of his adult life and wrote in both English and French.

Beckett's plays became the cornerstone of 20th-century theater beginning with ''Waiting for Godot,'' which was first produced in 1953. As the play's two tramps wait for a salvation that never comes, they exchange vaudeville routines and metaphysical musings - and comedy rises to tragedy.

Before Beckett there was a naturalistic tradition. After him, scores of playwrights were encouraged to experiment with the underlying meaning of their work as well as with an absurdist style. As the Beckett scholar Ruby Cohn wrote: "After 'Godot,' plots could be minimal; exposition, expendable; characters, contradictory; settings, unlocalized, and dialogue, unpredictable. Blatant farce could jostle tragedy."

For his accomplishments in both drama and fiction, the Irish author, who wrote first in English and later in French, received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1969. At the root of his art was a philosophy of the deepest yet most courageous pessimism, exploring man's relationship with his God… As illustrated by the final words of his novel, "The Unnamable": "You must go on, I can't go on, I'll go on." Or as he later wrote: "Try again. Fail again. Fail better."

In the Media

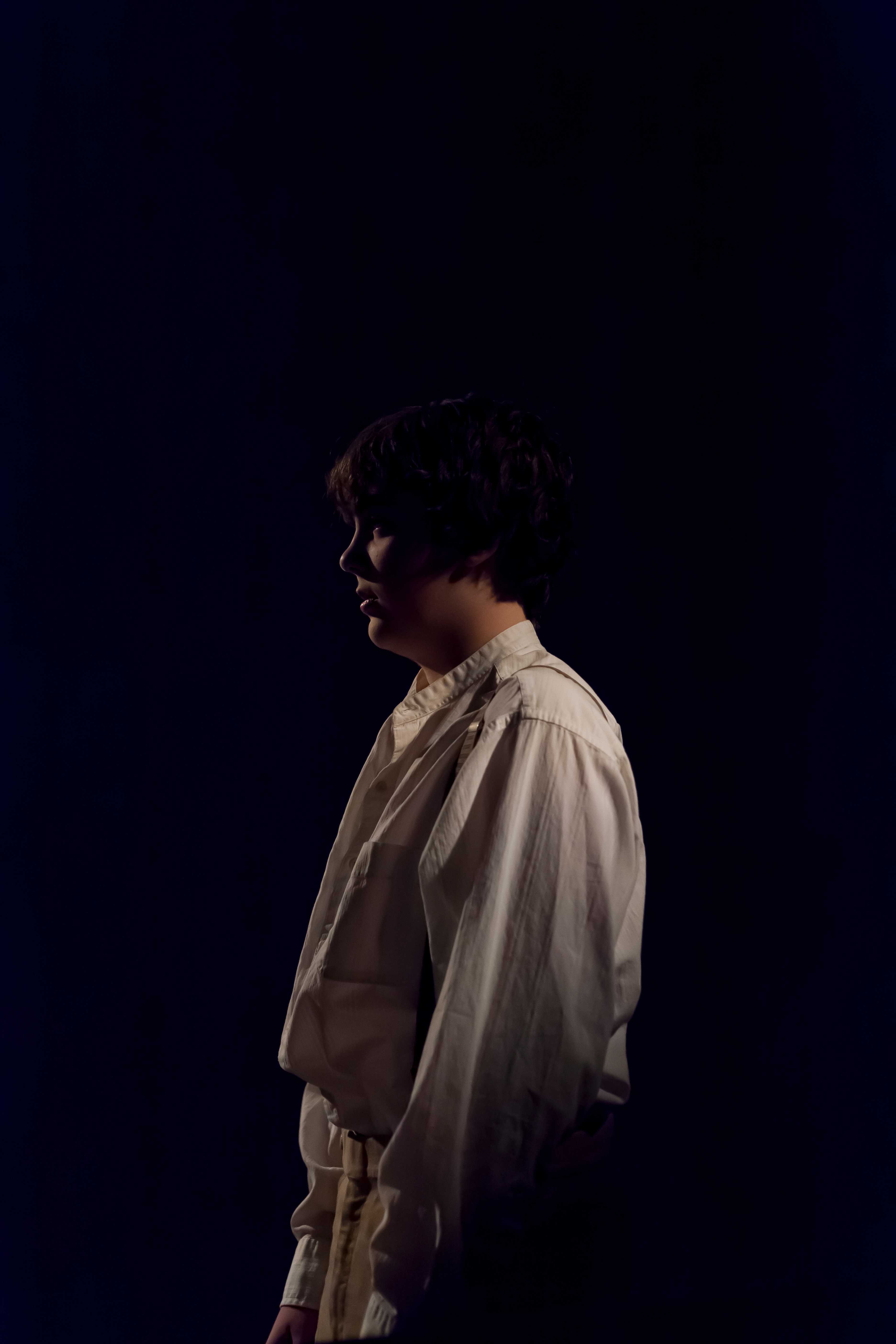

100 Creatives 2013: Ty Doran, Young Actor

May 3, 2013 |

Houston Press

| Joseph Capparella

Waiting for Godot Provides Another Successful Outing for The Catastrophic Theatre

March 27, 2013 |

Houston Press

| Jim Tommaney

Our Review of Catastrophic’s ‘Godot’

March 27, 2013 |

Houston Arts Week

| John DeMers